A few nice Citizenship and Freedom images I found:

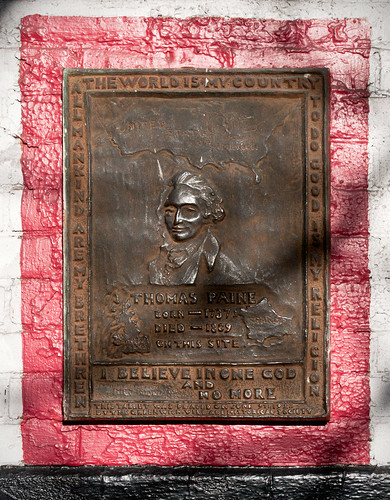

Thomas Paine Plaque (1923), 59 Grove Street, Greenwich Village, New York, New York

Image by lumierefl

Plaque installed by Greenwich Village Historical Society reads:

The world is my country

All mankind are my brethren

To do good is my religion

I believe in one God and no more

Thomas Paine (1737-1809) English political writer considered by some historians to be Father of the American Revolution because of Common Sense, pro-independence pamphlet published anonymously 10 Jan, 1776 • first 3 months 120K copies sold in American British Colonies (out of 2MM free inhabitants) • also wrote The Crisis pamphlet series (1776-1783), Rights of Man (1791) and The Age of Reason (1793-94), which argued against institutionalized religion and Christian doctrines

condemned as an atheist and denied American citizenship, Paine, 72, died obscure and penniless in a rooming house on this site, 8 June, 1809 • after request for burial in Quaker graveyard denied, buried under a walnut tree on his farm, New Rochelle, NY • 6 persons attended funeral • journalist Wm. Cobbett later transported Paine’s remains to England but was denied permission to bury them, remains subsequently lost • NY Citizen obituary stated Paine “lived long, did some good and much harm” • orator and writer Robert Ingersoll (1833 – 1899) wrote,

Thomas Paine had passed the legendary limit of life. One by one most of his old friends and acquaintances had deserted him. Maligned on every side, execrated, shunned and abhorred – his virtues denounced as vices – his services forgotten – his character blackened, he preserved the poise and balance of his soul. He was a victim of the people, but his convictions remained unshaken. He was still a soldier in the army of freedom, and still tried to enlighten and civilize those who were impatiently waiting for his death. Even those who loved their enemies hated him, their friend – the friend of the whole world – with all their hearts. On the 8th of June, 1809, death came – Death, almost his only friend. At his funeral no pomp, no pageantry, no civic procession, no military display. In a carriage, a woman and her son who had lived on the bounty of the dead – on horseback, a Quaker, the humanity of whose heart dominated the creed of his head – and, following on foot, two negroes filled with gratitude – constituted the funeral cortege of Thomas Paine.

recent biographies argue Paine was one of most important persons in modern history • the small wood framed house house in which he died replaced by building which now houses gay piano bar Marie’s Crisis, name inspired by Paine’s The Crisis • popular claim that parts of original house incorporated in current structure but Paine house actually stood where Grove St. now passes, was likely demolished in 1836 when street was widened • next door is Arthur’s Tavern (1937), jazz nightclub known as "Home of the Bird" because Charlie Parker frequently performed there

Boy Scout Monument

Image by dbking

Boy Scout Memorial

Boy Scout Memorial

Location: 15th Street, NW between E Street and Constitution Avenue

Erected: 1964

Sculptor: Donald DeLue

Architect: Willam Henry Deacy

The memorial to the Boy Scouts of America is the only memorial in Washington to commemorate a living cause. It was constructed at no expense to the government. The funds were raised from each Scout unit and each donor signed a scroll that was later placed in the pedestal of the statue.

During the 50th Anniversary Year of Scouting (1959), a proposal was made to establish the memorial on the site of where the first Boy Scount Jamboree in Washington, D.C. was held. Lyndon B. Johnson, who was the Senate majority leader at the time, introduced the measure to the Senate. The memorial was eventually unveiled in a ceremony on November 7, 1964. The statue was accepted for the country by Associate Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark, who noted it was his fiftieth anniversary as an Eagle Scout.

The bronze statue consists of three figures: a Boy Scout, a woman and a man. Each figure symbolizes the idea of the great and noble forces that are an inspiring background of each Scout as he goes about the business of becoming a man and a citizen.

The male figure symbolizes physical, mental and moral fitness, love of country, good citizenship, loyalty, honor, courage and clean living. He carries a helmet, a symbol of masculine attire and a live oak branch, a symbol of peace and of strength.

The female figure symbolizes enlightenment with the light of faith, love of God, high ideals, liberty, justice, freedom, democracy and love of fellow man; symbolizing the spiritual qualities of good citizenship. She holds high the eternal flame of God’s Holy Spirit.

The figure of the Boy Scout represents the hopes of all past, present and future scouts around the world and the hopes of every home, church and school that all that is great and noble in the Nation’s past and present will continue to live in them and through them in many generations to come.

A small pool in front of the memorial represents the honor of those children who joined the Boy Scouts of America.

Boy Scout Oath or Promise

On my honor, I will do my best

To do my duty to God and my country and to obey the Scout Law;

To help other people at all times;

To keep myself physically strong, mentally awake and morally straight.

John Randolph, a Founder of the American Colonization Society

Image by elycefeliz

In 1816 the formation of the American Colonization Society gave organizational form to the belief that blacks would be better off settled in colonies back in Africa.

Men including Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John Randolph supported the society’s goals. Abraham Lincoln wold as well. They did so out of a belief that the prejudice of race was so strong in America that free blacks would never successfully integrate into society, and that slavery itself was a "necessary evil" that warped Southern institutions and might best be abolished gradually.

from The Civil War, Louis Masur

The American Colonization Society (in full, The Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America), founded in 1816, was the primary vehicle to support the "return" of free African Americans to what was considered greater freedom in Africa. It helped to found the colony of Liberia in 1821–22 as a place for freedmen. Its founders were Henry Clay, John Randolph, and Richard Bland Lee.

Paul Cuffee, a wealthy mixed-race New England shipowner and activist, was an early advocate of settling freed blacks in Africa. He gained support from black leaders and members of the US Congress for an emigration plan. In 1811 and 1815-16, he financed and captained successful voyages to British-ruled Sierra Leone, where he helped African-American immigrants get established. Although Cuffee died in 1817, his efforts may have "set the tone" for the American Colonization Society (ACS) to initiate further settlements.

The ACS was a coalition made up mostly of Quakers who supported abolition, and slaveholders who wanted to remove the perceived threat of free blacks to their society. They found common ground in support of so-called "repatriation". They believed blacks would face better chances for full lives in Africa than in the U.S. The slaveholders opposed abolition, but saw repatriation as a way to remove free blacks and avoid slave rebellions. From 1821, thousands of free black Americans moved to Liberia from the United States. Over 20 years, the colony continued to grow and establish economic stability. In 1847, the legislature of Liberia declared the nation an independent state.

Critics have said the ACS was a racist society, while others point to its benevolent origins and later takeover by men with visions of an American empire in Africa. The Society closely controlled the development of Liberia until its declaration of independence. By 1867, the ACS had assisted in the movement of more than 13,000 Americans to Liberia. From 1825-1919, it published a journal, the African Repository and Colonial Journal. After that, the society had essentially ended, but did not formally dissolve until 1964, when it transferred its papers to the Library of Congress.

The arguments propounded against free blacks, especially in free states, may be divided into four main categories. One argument pointed toward the perceived moral laxity of blacks. Blacks, it was claimed, were licentious beings who would draw whites into their savage, unrestrained ways. The fears of an intermingling of the races were strong and underlay much of the outcry for removal.

Along these same lines, blacks were accused of a tendency toward criminality. Still others claimed that the supposed mental inferiority of African Americans made them unfit for the duties of citizenship and incapable of real improvement. Economic considerations were also put forth. Free blacks were said to threaten jobs of working class whites in the North.

Southerners had their special reservations about free blacks, fearing that the freedmen living in in slave areas caused unrest to slaves, and encouraged runaways and slave revolts. They had racist reservations about the ability of free blacks to function. The proposed solution was to have free blacks deported from the United States to colonize parts of Africa.

Despite being antislavery, Society members were openly racist and frequently argued that free blacks would be unable to assimilate into the white society of this country. John Randolph, one famous slave owner, called free blacks "promoters of mischief." At this time, about 2 million African Americans lived in America of which 200,000 were free persons of color (with legislated limits). Henry Clay, a congressman from Kentucky who was critical of the negative impact slavery had on the southern economy, saw the movement of blacks as being preferable to emancipation in America, believing that "unconquerable prejudice resulting from their color, they never could amalgamate with the free whites of this country. It was desirable, therefore, as it respected them, and the residue of the population of the country, to drain them off". Clay argued that because blacks could never be fully integrated into U.S. society due to "unconquerable prejudice" by white Americans, it would be better for them to emigrate to Africa.

The ACS purchased the freedom of American slaves and paid their passage to Liberia. Emigration was offered to already free black people. For many years the ACS tried to persuade the US Congress to appropriate funds to send colonists to Liberia. Although Henry Clay led the campaign, it failed.

Since the 1840s Lincoln, an admirer of Clay, had been an advocate of the ACS program of colonizing blacks in Liberia. In an 1854 speech in Illinois, he points out the immense difficulties of such a task are an obstacle to finding an easy way to quickly end slavery.[14]

Early in his presidency, Abraham Lincoln tried repeatedly to arrange resettlement of the kind the ACS supported, but each arrangement failed. By 1863, following the use of black troops, most scholars believe that Lincoln abandoned the idea. Biographer Stephen B. Oates has observed that Lincoln thought it immoral to ask black soldiers to fight for the US and then to remove them to Africa after their military service. Others, such as the historian Michael Lind, believe that as late 1864 or 1865, Lincoln continued to hold out hope for colonization, noting that he allegedly asked Attorney general Edward Bates if the Reverend James Mitchell could stay on as "your assistant or aid in the matter of executing the several acts of Congress relating to the emigration or colonizing of the freed Blacks." Mitchell, a former state director of the ACS in Indiana, had been appointed by Lincoln in 1862 to oversee the government’s colonization programs. In his second term as president, on April 11, 1865, Lincoln gave a speech supporting suffrage for blacks.

Three of the reasons the movement never became very successful were the objections raised by free blacks and abolitionists, the scale and costs of moving many people (there were 4 million freedmen in the South after the Civil War), and the difficulty in finding locations willing to accept large numbers of black newcomers.